Bain Capital

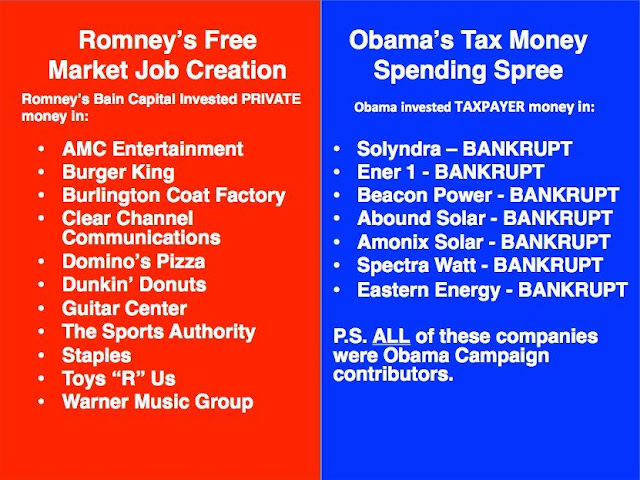

I saw this posted on Facebook by a Tea Bagging old high school friend of mine. I'm not going to get into the Theory A versus Theory B argument but to say that in a capitalistic society, sometimes companies go under. It's the nature of the beast.

However, the claim that Bain created jobs or left companies in a better-off position than when they began their 'investment' is false in a number of ways.

Bain Capital, which forced in-trouble companies to take out massive amounts of debt so Bain could get paid for their advice? That Bain Capital?

Like the Bain Capital that sold AMC theaters to the Chinese? You know, to keep America America? http://goo.gl/arSYj

Or Burger King: http://goo.gl/LVEAq

Enter — ta-da! — private equity. In 2002, Goldman Sachs, along with two private equity firms, TGP and ... hmmm ...Bain Capital, teamed up to buy Burger King. This is exactly the kind of situation private equity firms like to trumpet: taking over a downtrodden company and nursing it back to health. And to get them their due, Burger King’s new owners did some good, stabilizing both the company and the franchisees, many of whom were in worse shape than Burger King itself.But the private equity investors also cut themselves an incredibly sweet deal. Their $1.5 billion purchase price included only $210 million of their own money; the rest was borrowed. They immediately began taking out tens of millions of dollars in fees. Four years later, they took Burger King public. But, first, they rewarded themselves with a $448 million dividend. In all, according to The Wall Street Journal, “the firms received $511 million in dividend, fees, expense reimbursements and interest” — while still retaining a 76 percent stake.Does it need to be said that Burger King was soon back to its old struggling self? Or that the solution, once again, was to sell to another private equity firm? Of course not! In 2010, Bain, Goldman and TPG cashed out, selling Burger King to 3G Capital, for $3.3 billion. In sum, the original private equity troika reaped a fortune by selling a company that was in nearly as much trouble as it had been when they first bought it. Surely this represents the apotheosis of financial engineering.

Or the massive debt held by BCF: http://goo.gl/PQBfv

Burlington Coat Factory Warehouse Corp., the discount clothing-store operator, pulled $1.5 billion of debt financing it planned to repay borrowings and fund a dividend to owner Bain Capital LLC, according to eight people familiar with the negotiations.

Or, were you referring to Clear Channel? http://goo.gl/AWVrr

Consider Bain Capital’s Thomas Lee Partners’ $26 billion acquisition of Clear Channel Communications — home of Rush Limbaugh — and his $400 million, eight-year syndication deal inked in 2008. This takeover has turned a company that formerly earned net income of nearly $1 billion into a money-loser (almost $4.7 billion in cumulative losses), resulted in thousands of layoffs, extracted millions in fixed management fees, and recently resulted in a multi-billion special dividend for the two PE owners paid for by highly risky borrowing.

Or, Dominos Pizza: http://goo.gl/RT4hV

In 1998 the acquisition of Domino's Pizza was "a huge deal" for Bain Capital, the Boston Globe reported in January 2012. The company wasn't in trouble, nor was it a turnaround case, but it was a good investment for Bain. While Domino's grew its revenues and earnings under Bain, its debt also rose to $1.5 billion, leaving interest payments that eat up half its profits each year.

Or, Dunkin Donuts: http://goo.gl/ncdxI and http://goo.gl/KpCQY

as a P.R. rep for Bain was happy to inform me: The company has cut itself loose from Dunkin’, having just sold off the last of its shares a matter of weeks ago (it went public in July 2011), completing the private equity cycle of life. After growing the stock price, while hanging the company with $1.25 billion in debt, Bain sold its stake in the company on August 15, making a tidy $600 million.And

If you borrow billions to buy Dunkin' Donuts and the firm flourishes post-takeover, that's one way for investors to get paid. But another way is getting Dunkin' to take out a $1.25 billion bank loan to hand its investors $500 million in tribute payments.

It's hard to imagine anything that's dumber, from the standpoint of trying to grow a business, than taking out a billion-dollar loan to pay a dividend – one buddy of mine on Wall Street used the word "retarded" – but for a private equity firm and its investors, that might very well be a smart way to get your investors paid.

Or, Guitat Center: http://goo.gl/BGy6L

Or, Sports Authority: http://goo.gl/TPxpBFender's debt problem consists not only of what it owes but what it is owed. The company is currently owed $11 million by its biggest customer, musical instruments retailer Guitar Center. Fender's fortunes are intrinsically linked to Guitar Center. The retailer accounts for nearly a sixth of Fender's annual sales, and Fender CEO Larry Thomas had previously held the same position at Guitar Center. Thomas was responsible for taking Guitar Center public and then selling it to Bain Capital in 2007. Until the sale, Guitar Center was also partially owned by Weston Presidio.Guitar Center has been losing money every year since, making it a nightmare investment for Bain Capital. Moody's rated it a lowly Caa2 (defined as "poor standing and subject to very high credit risk") in November 2010. In its report, the ratings firm stated that "the company's capital structure is unsustainable over the medium term at current levels of operating performance, and hence the probability of a default has increased."

There's only one problem with Romney's story: It doesn’t describe most of what private equity firms actually do. The companies Romney holds up as successes – Staples, Sports Authority et al. – were not Bain private equity deals; they were venture capital investments in companies that Bain neither owned nor ran. All well and good: Venture capital is a good thing – essential for funding the growth of new and developing companies. But Romney didn't make his fortune through venture capital; he made it through private equity – and private equity, as President Obama pointed out this week, is a very different proposition. "Their priority is to maximize profits," the president said of PE firms, and "that’s not always going to be good for businesses or communities or workers.Staples, as seen at the above link, (or this one if your eyes don't go up: http://goo.gl/TPxpB)

There's only one problem with Romney's story: It doesn’t describe most of what private equity firms actually do. The companies Romney holds up as successes – Staples, Sports Authority et al. – were not Bain private equity deals; they were venture capital investments in companies that Bain neither owned nor ran. All well and good: Venture capital is a good thing – essential for funding the growth of new and developing companies. But Romney didn't make his fortune through venture capital; he made it through private equity – and private equity, as President Obama pointed out this week, is a very different proposition. "Their priority is to maximize profits," the president said of PE firms, and "that’s not always going to be good for businesses or communities or workers.Or Toy 'R Us (KB Toys): http://goo.gl/OSlMF

A Bain partnership bought KB Toys in 2000, putting up $18 million and borrowing the rest, $302 million, the Times reported. Less than a year and a half later, KB Toys borrowed more to pay Bain and its investors — which would have included Romney — an $85 million dividend. (That dividend was part of a $121 million stock redemption, funded in part by $66 million in bank loans, Bloomberg reported based on other news coverage.) Bain partners made a 370 percent return, but left the company heavily in debt.Or Warner Music Group, after $700 million dollars in debt added after being acquired by Bain Capital and their partners: http://goo.gl/b0wc8 and http://goo.gl/izIem

Private-equity firms Thomas H. Lee Partners LP, Bain Capital LLC and Providence Equity Partners hold the majority of the company’s common stock, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings grade Warner Music B+ with a “negative” outlook, while Moody’s Investors Service has a Ba3 ranking, one step higher, with a review for a downgrade, Bloomberg data show. High-yield, high-risk, or junk, debt is rated below Baa3 by Moody’s and lower than BBB- by S&P.

Comments